‘IT IS NOT KNOWN IF BY LICENCE OR NOT’:

UCKFIELD’S MEDIEVAL BOROUGH AND MARKET.

The quantity of painstaking research published by Uckfield and District Preservation Society over many years – in seven annual volumes of HINDSIGHT, quarterly newsletters before that and several books – should disprove the old prevalent folk-belief that Uckfield has no history. But reference in my title to its status as a borough and market in the Middle Ages may invite suspicion of the opposite extreme: extravagant claims of an exalted past. Scepticism may be the reader’s reaction. Here the evidence will be presented and these two features discussed and evaluated, to introduce the economy and society of the time and to highlight current interests of historians.

Uckfield’s conversion in local government from parish to town council occurred in recent decades, though its period as an urban district from 1894 to 1934 will be remembered. There is no borough charter of any date on display in the Civic Centre or elsewhere. Likewise, Sally Pearce’s research has established that a market appeared between 1792 and 1849, continuing until the Second World War and undergoing various changes.1 Clearly these two institutions do not have unbroken links with earlier centuries!

The first mention of Uckfield’s market, in 1220, is also the earliest known record of the place-name. This is an entry on the Great Roll of the Pipe Office, part of the Exchequer, that the Archbishop of Canterbury owes one palfrey (five marks, or 67s.8d.) for holding a market every Wednesday on his manor at Uckfield.2 There is an indication of major change to the market even as early as the late thirteenth century. The custumal of the Archbishop’s manors, including South Malling in which Uckfield lay, dated probably about 1285 but with some earlier information, notes that Uckfield’s market is now every Monday, with another at Wadhurst on Saturdays ‘but it is not known if by licence or not’. This suggests a serious break in both living memory and record-keeping, surprising in the case of such a magnate as the Archbishop. However, the same passage states that he ‘has a full liberty in them of pillory, tumbrel and other things pertaining to a regality’: in other words, complete jurisdiction over the market.3

It is this custumal, a list of free and unfree tenants owing payments and services to their manorial lord the Archbishop, which is also the sole known evidence of Uckfield’s borough status. Under Uckfield, after listing free tenants the document identifies twelve burgesses, almost all holding one messuage of land. In order of appearance, they are: Peter le Tanner, Reynold at Dune, Maud de Marsefeud, Robert de Soler’, Dyn de Uckefeud, Robert le Nyweman, Simon son of Nicholas, Simon de Luddesham, Roger le Webbe, Simon le Webbe, Roger le Cuherd and Alan le Plater (an interesting mix of early surnames based on occupations, places and other descriptions). It was Robert who held two messuages rather than the usual single, while Alan held an unspecified ‘piece of land upon which a certain part of his house stands….’ The sizes or earning capacities of these messuages varied considerably. Simon le Webbe and Roger le Cuherd paid just ½d. for theirs; the other two Simons and Roger le Webbe paid a penny each. Dyn was charged the sum of 2s. 3%d.

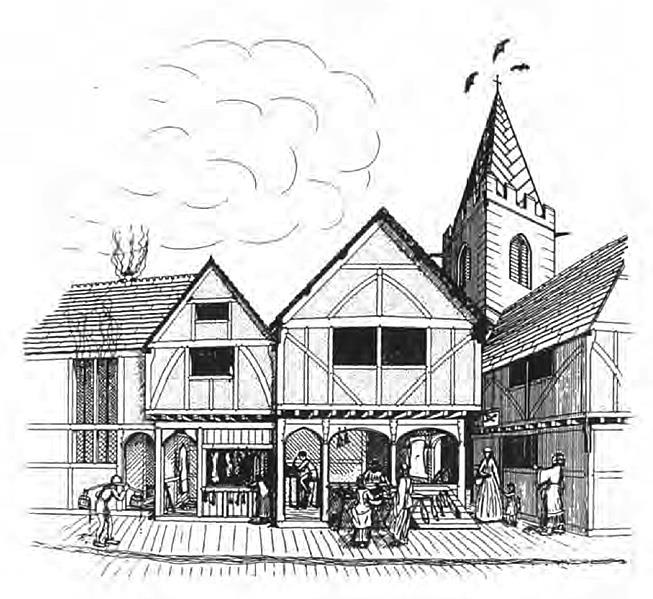

Original drawing by Robert Waterhouse. Reproduced by kind permission from the publishers of Medieval Housing by Jane Grenville (Leicester University Press, an Imprint of Continuum, 1997)

Alan owed 2d. for his land; perhaps his house extended to include one or both of the shops he also held. Dyn likewise held a shop, too; in all seven individuals had a total of eleven shops, charged at a standard 6d. per shop.4 Burgesses and shopkeepers also had other types of holdings within the borgh of Uckfield and sometimes elsewhere too. Detailed analysis of these warrants further research; this article is confined to two urban characteristics of Uckfield at this time.5

It will be helpful to discuss what made and what proved a borough, in Sussex and more generally. A vivid description of its essence comes from the pens of two eminent topographers of medieval England, Professors Maurice Beresford and Herbert Finberg:

‘We have in mind here the fact that the medieval burgage plot commonly took on a characteristic shape – long and narrow, with one short side abutting on the market place or another principal street of the borough. The grouping of these burgages together, with roughly similar lengths, made for a compact envelope, delimiting the borough territory even when – as in the majority of medieval English boroughs – there were neither walls nor other defences…Whenever such a pattern of plots is noticed, it should give rise to speculation, which is not the same thing as assertive proof.’6

The key feature of boroughs seen in economic and social terms was the presence of burgesses on burgages with privileges such as exemption from market tolls but also paying rents, often one shilling a year, much higher than for the equivalent area of agricultural land, and royal taxes on assessed wealth at a greater rate than other individuals.7

The situation in Uckfield evidently differed from some of these generalizations. None of the dozen burgesses paid the round shilling, only two were assessed for more, while their tenements were labelled messuages or a mere piece, rather than the expected burgages.

We are warned not to confuse legal use of the term borough with looser topographical variants borgh, burgh or even borough in Sussex, Kent and elsewhere: witness the administration of South Malling manor and the lay subsidies of tenths and fifteenths taxation. These units were often also termed as tithings and were grouped into the hundreds of such counties.8

Like Uckfield, Battle qualifies as a borough solely on the mention of burgesses there. Yet the entry in the chronicle of the Abbey, c.1180, has proved to be more assertive and memorable than the unread custumal listing for Uckfield! ‘On account of the very great dignity of the place, the men of this town are called burgesses.’9 Pevensey, too, relies on the presence of burgesses to be recognized. Representation at the eyre court of 1248 as a borough with its own jury is the main evidence for Bramber, Midhurst, Seaford and Steyning. Mention in the Burghal Hidage of c.900 applies to Burpham and Lewes. Charters survived only for Chichester, Hastings, Lewes, Rye and Winchelsea in Sussex. Taxation as a borough, reference to status in Domesday Book, Close Rolls and other documents are further clues, which add Arundel, East Grinstead, Horsham and Shoreham to the county’s tally.10 Thus charters, essential to popular conceptions of boroughs, are by no means the limit of evidence. Even when granted, they may date considerably later than the start of borough status, and might be lost or dispensed with for various reasons.11

A borough was a special sort of town, therefore, distinguished by freedom and privileges for its burgesses. A formal weekly market might be regarded, by contrast, as special regulation of a widespread essential and enduring practice. Urban and trading life could and did flourish outside as well as inside these legal entities of boroughs and markets. But to the common background of supply and demand of local inhabitants, these institutions added other motives such as promotion, order and profit on behalf of lords and the crown. It took some time after the Norman Conquest for the purpose of a legal market to become clear. Removing trading from Sundays, commonly favoured because communities conveniently met for worship then, was one reason. Market towns and villages increased in number with population growth, consequential greater purchasing power (in total but not always per head) and rising agricultural output and more purchasing power. The several hundred smaller trading places like Uckfield would have related to not only their rural vicinity but also the major towns and cities depending on wider and more diverse economic links.12

Uckfield was not established as borough and market to compete blatantly with neighbouring places, which sometimes happened. It was situated fairly centrally within the manor of South Malling to which it belonged, and those functions added to the manor’s other activities. The fellow market, Wadhurst, lacked burgesses or other borough features and traded on another day. Indeed, the manor continued to purchase from an outside market, Lewes. Uckfield possessed the manor’s only mills specifically identified as used for the fulling of cloth, so that its river was then known as the Fuleburne. Here too were the manor’s only known shops, though these may equally have been workshops as retail premises and perhaps merely temporary structures as those at Heathfield may have been.13

Uckfield’s Wednesday and succeeding Monday market was an early such foundation in the Weald, followed (or, if a quick failure, itself replaced) by complementary markets around it at respectful distances. To the north, East Grinstead had a Monday market and another changing from Sunday to Saturday. Parrock in Hartfield may be a market too. Cuckfield changed from Tuesday to Monday by 1312. Frant’s market was also on Tuesdays; Hailsham’s on Wednesdays.

Apart from Lewes, Ringmer’s Tuesday market from 1283 and Mayfield’s Thursday one from 1261 (taking other days in the fourteenth century) escape mention in the South Malling custumal. They may not have been relevant to the document; the Uckfield and Wadhurst markets appeared merely as stray references under the borgh of Wellingham! Perhaps Ringmer’s was too late in date, while Mayfield’s may have been in an area such as Bivelham outside the manor. During the fourteenth century, further markets appeared in Cliffe, Ditchling, Heathfield and Lindfield, perhaps at Maresfield and Rotherfield as well.14

No references to Uckfield as a borough or market in the Middle Ages or the early modern period are yet known after 1300. With the post-plague contraction of population and consolidation of certain towns only, many markets disappeared because of these national trends. Some failed even sooner, because they were uncompetitive or simply surplus in the locality. The blank in Uckfield’s case cannot prove either survival or collapse; it can only suggest the latter but may simply mark the random frontier of our present knowledge. Beresford and Finberg readily admitted to their ‘haphazard scrutiny’ of sources, themselves surviving through ‘vagaries and chances’: entirely excusable reasons for not noticing the borough of Uckfield. Thus, it can no longer be said that ‘no archbishop, it is true, has yet been found planting a town’.15

Uckfield may be considered limited as an independent community since in the church’s eyes it continued as a mere chapelry in the south-west corner of Buxted parish until 1846, though in practice there was an element of autonomy. Likewise Crawley, an even earlier market foundation in the Weald, remained a chapelry to Slaugham (though also a rectory in its own right) until 1901, though about 1510 it had absorbed the adjacent defunct parish of Shelley. Curiously, Uxbridge in Middlesex, sometimes confused linguistically with Uckfield, itself a market from 1170 but not a borough, was another persistent chapelry until 1842, within Hillingdon parish. The fact of urban development over centuries clashed in all three places with the vested interests of ecclesiastical property rights.16

It is tempting to look now in the opposite direction, for the origins of Uckfield. 1220 is the oldest known documentary reference, as mentioned earlier. Was this the creation of the town? This is the orthodox view: a new centre during a time of population expansion into areas comparatively lightly exploited.17 The place-name Uckfield means ‘Ucca’s open land’, perhaps dating from an early phase of Anglo-Saxon settlement, often on the edge of relief districts like the Low and High Weald boundary, suggesting more intensive encroachment on mainly grazing land.18 Ucca himself remains completely unknown; whether local founding leader, a lone wanderer or settler of whatever century may be equally valid fancies. Dating the stages between naming this spot, inaugurating cultivation and residence or the emergence of urban characteristics is also wide open to speculation.

A more solid basis for gauging the age of intensive settlement may be the degree to which free and unfree tenants and free and unfree land had become mixed. Bondland must mostly have been allocated before the thirteenth century, when assarting of land from waste (bearing lighter service obligations) was underway in South Malling manor. Local historians of Wadhurst, led by John Lowerson, have already investigated this situation. Perhaps there are comparable places where the date of settlement may be known from more abundant sources, so that the rate of change over time can be calculated.19

The chronology of South Malling manor as a whole is fuller. At the meeting of his council held at Kingston in 839, King Egbert of Wessex restored the territory to Archbishop Ceolnoth. It had earlier been granted by King Baldred of Kent, expelled by Egbert in 825, whose predecessor was reigning in 807. One theory explaining the ‘multiple estate’ structure of this manor attributes its beginnings to Celtic times, but it was a convenient form of administration adaptable to changing conditions in society.20

But to seek out the remotest possible origins can obscure the more significant later development. The French historian François Simiand condemned three ‘idols’ of traditionally-minded scholars, including the ‘idol of origins’ which entailed studying things when they were beginning rather than when they were important.21

Whether or not that particular judgment is justified, there is much dynamism at present in medieval social history,22 and much more to uncover. Uckfield has a part in that past story and that future exploration.

BRIAN PHILLIPS

References

- S Pearce, ‘Was Uckfield a market town?’, Uckfield & District Preservation Society Newsletter (October 1989), pp.11-13; B Fuller and B Turner, Bygone Uckfield (Chichester, 1988), no.29; B Hart and D Nunn, Uckfield: Portrait of a Wealden Town (Uckfield, 1988), p.9.

- Public Record Office E372/64 rot.5 m.1d, printed as Pipe Roll Society vol.85 (1987), p.69.

- Canterbury Cathedral Archives E24, printed as B C Redwood and A E Wilson, ed., Custumals of the Sussex manors of the Archbishop of Canterbury, Sussex Record Society, vol.57 (1958), p.95.

- SRS 57, p.76-77.

- An outline study of holdings in Uckfield and the rest of South Malling is H E Hallam, ‘Social structure: South-eastern England’, ch.6 of Hallam, ed., The agrarian history of England and Wales, vol.2, 1042-1350 (Cambridge, 1988), pp.621-631.

- M W Beresford and H P R Finberg, English medieval boroughs: a handlist (Newton Abbot, 1973), p.35.

- Beresford & Finberg, Boroughs, pp.26, 28; M W Beresford, New towns of the Middle Ages: town plantation in England, Wales and Gascony (1967), pp.63-64, 90.

- Beresford & Finberg, Boroughs, p.26 & n.16; SRS 57; W Hudson, ed., The three earliest subsidies for the county of Sussex in the years 1296, 1327, 1332…, Sussex Record Society, vol.10 (1909), esp. pp.xviii-xxvii.

- Quoted in Beresford, New towns, p.493. See also E Searle, Lordship and community : Battle Abbey and its banlieu 1066-1538 (Toronto, 1974), p.79.

- Beresford, New towns, pp.257, 492-498; Beresford & Finberg, Boroughs, pp.169-172.

- Beresford, New towns, pp.198-207; Beresford & Finberg, Boroughs, pp.23-24.

- R H Hilton, English and French towns in feudal society: a comparative study (Cambridge, 1992), pp.40, 128; R H Britnell, The commercialisation of English society 1000-1500 (2nd ed., Manchester, 1996), pp.14-19; D L Farmer, ‘Marketing the produce of the countryside, 1200-1500: markets, fairs, and transport’, ch.4 of E Miller, ed., AgHEW, vol.3, 1348-1500 (Cambridge, 1991), pp.334-335; Britnell, ‘The proliferation of markets in England, 1200-1349’, Economic History Review, 2nd series, vol 34 (1981); Britnell, ‘Urban demand in the English economy, 1300-1600’ and C Dyer, ‘…A summing up’, in J A Galloway, ed., Trade, urban hinterlands and market integration c.1300-1600, Centre for Metropolitan History, Working Papers Series, no.3 (2000).

- SRS 57, pp.75, 77, 114; J Schofield and A Vince, Medieval towns (1994), p.135; P F Brandon, ‘New settlement: South-eastern England’, ch.3 of AgHEW, vol.2, p.187; M Gardiner,’The geography and peasant rural economy of the eastern Sussex High Weald, 1300-1420’, Sussex Archaeological Collections, vol.134 (1996), p.134.

- Gardiner, ‘High Weald’, p.133; J Bleach and M Gardiner, ‘Medieval markets and ports’, in K Leslie and B Short, ed., An historical atlas of Sussex (Chichester, 1999), pp.42-43, 147 (which omits or disregards Uckfield’s borough status and original market-day).

- Beresford & Finberg, Boroughs, pp.32, 34; Beresford, New towns, p.95.

- P Brandon and B Short, The South East from AD1000 (1990), p. 123; Bleach & Gardiner, ‘Medieval markets’, p.42; W Page, ed., The Victoria History of the county of Sussex (1940), pp.146-147; Beresford, New towns, p.466.

- Brandon, ‘New settlement’, p.188; Bleach & Gardiner, ‘Medieval markets’, p.42.

- A Mawer and F M Stenton, The place names of Sussex, vol.2 (Cambridge, 1930), p.396; M Gelling, ‘The present state of English place-name studies’, The Local Historian, vol.22 (1992), p.121.

- F R H Du Boulay, The lordship of Canterbury: an essay on medieval society (1966), p.180; J Lowerson, ‘”Within the wood”: some aspects of medieval Wadhurst’, Sussex History, vol.1 no.7 (1979), esp. pp.5-6; Wadhurst Local History Group, Within the wood: medieval Wadhurst, University of Sussex Centre for Continuing Education Occasional Paper 19 (1983), esp. pp.11-14; R Faith, The English peasantry and the growth of lordship (1999 ed.), pp.262-263.

- Du Boulay, Lordship of Canterbury, pp.31-32; F M Powicke and E B Fryde, ed., Handbook of English chronology, (2nd ed., 1961), p.9; C R Cheyney, ed., Handbook of dates for students of English history (Cambridge, 1996 ed.), p.12; G R J Jones, ‘Multiple estates and early settlement’, in P H Sawyer, ed., Medieval settlement: continuity and change (1976); Faith, English peasantry, pp.11-14.

- Beresford, New towns, p.324; P Burke, ‘Introduction’, to Burke, ed. Economy and society in early modern Europe: essays from Annales (New York, 1972), p.4.

- For example, see C Dyer, ‘How urban was medieval England?’, History Today, vol.47 no.1 (January 1997) and M Bailey, ‘Trade and towns in medieval England: new insights from familiar sources’, The Local Historian, vol.29 (1999).